Home » Our history

Our history

Aveng is proud of its rich history over the last 135 years, rooted in the development of the South African economy. Our formation reveals the uniting of strong principles, innovation and determination. It is a story of converging disciplines and personalities, and it is one that is proudly recounted.

Explore the years

-

1889

22 July 1889The pioneers of success

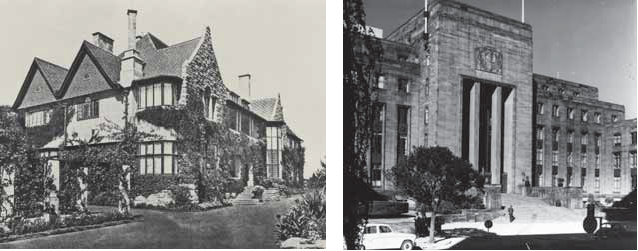

James Thompson became an apprentice carpenter in Durban at the age of 12. He eventually found his way to Johannesburg where he began working for Kemp and Wishard. In 1889 he set up his own building and carpentry business: J Thompson, Carpenter and Builder. Thompson offered his clients the strong values that were to define his legacy: honesty, reliability and excellence, bringing public interest to a family business with an established set of principles. By this point, Thompson had ensured that his business philosophy had been passed down to his sons, Mark and James.

From modest beginnings he developed a network of loyal and trusting customers, and his talents earned plaudits from the likes of Sir Herbert Baker, who declared Thompson “the best builder in South Africa”.

-

1911

22 July 1911Grinaker lays the foundations

Ole Grinaker, a Norwegian engineer, arrives in South Africa in 1911 and would eventually establish one of the most successful construction companies in the country. Grinaker was to become an influential figure in local construction.

The construction sector is particularly bound to the ebb and flow of the global economy and tends to capitalise on financial booms and contract in the wake of recession. By facing adversity head on, both Thompson and Grinaker would lay the foundations for what would become the Aveng Group.

-

1939

22 July 1939Schwarer’s winning formula

By the start of the Second World War, another entrepreneur was making a name for himself in the gold capital of the world. Harold “Blue” Schwarer founded his own company, Lewis Construction. While Thompson’s values reflected the duties of the provider, Schwarer focused more on customer satisfaction and delivery, which proved to be his own winning formula.

As director of Lewis Construction, Schwarer instilled solid business principles in all his employees.

-

1950

22 July 1950Steel comes to the fore

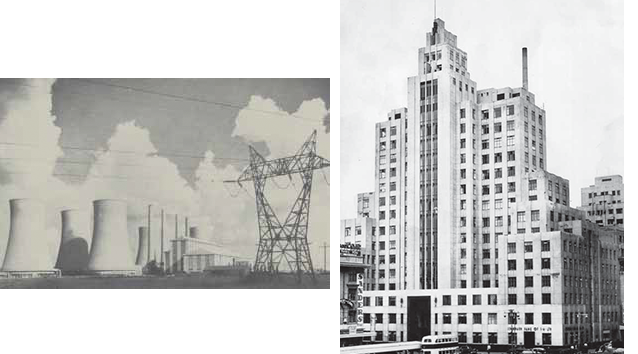

The 1950s marked renewed interest in the steel industry, which had yet to prosper since the first factories and workshops – smelting iron, reworking scrap metal and other related processes – were established at the turn of the century.

Schwarer established the Steeledale Reinforcing and Trading Company in 1951 in response to the demand placed on the construction industry by the post-war shortage. The company served as a steel merchant and offered the cutting and bending of reinforcing steel. Under Schwarer’s stewardship it diversified and grew substantially.

-

1955

22 July 1955Moolmans paves the way

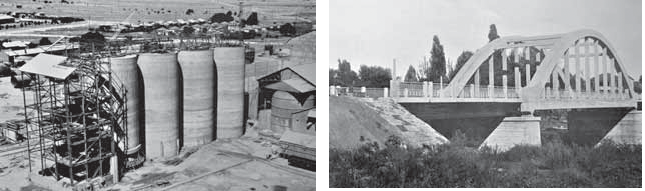

Mike and Cedric Moolman, who founded the company that was to become Aveng Moolmans, began building roads, railways and runways that connected nations – paving the way for a bold new era. They facilitated the logistical challenges that lay between mining and development, such as the transportation of enormous quantities of coal and rocks.

-

1963

22 July 1963LTA merges and lists

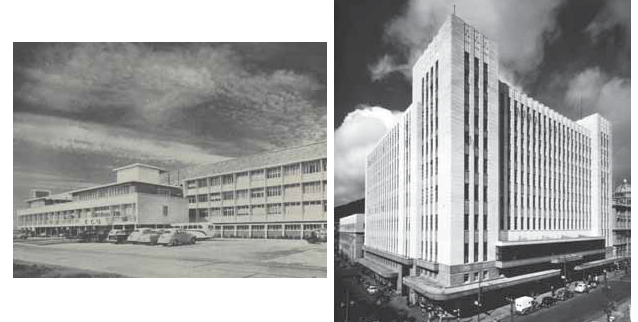

The pursuit of excellence in one area encourages success in others. This is what motivated the establishment of the Amalgamated Construction and Contracting Company (Amco). Formed in 1963, it began life as a group of about 50 subsidiaries and affiliates, which ultimately united into one entity. Amco shifted its focus to civil engineering work within the mining sector.

In 1965, James Thompson Limited merged with Lewis Construction, Steeledale Reinforcing and Amco to form LTA. The company was listed on the JSE and expanded rapidly, winning prominent contracts nationwide. LTA acquired a more diverse portfolio, including the establishment of an electrical and process engineering division and the acquisition of a mechanical engineering and piping business.

-

1975

22 July 1975McConnell Dowell gains momentum

Capitalising on the new wave of infrastructure development, two New Zealand entrepreneurs – Malcolm McConnell and Jim Dowell – had already established a multinational engineering and construction business by 1975, boasting operations not only in their homeland but also in Australia, Indonesia and Hong Kong. McConnell Dowell, as it was called, would soon establish ties within other specialised industries, increasing their geographical presence year by year.

-

1980

22 July 1980LTA diversifies

As the 1980s approached, LTA began to diversify, forming a new mechanical, process and electrical engineering division. The client base grew to include the chemical, mineral process and petrochemical industries. The decision to incorporate these new skills served as the point of departure for the future Aveng Engineering. South Africa’s growing economy and ambitious government infrastructure development programmes also required investment in new energy projects.

-

1990

22 July 1990Training key for Moolmans

In the mining sector, Moolmans began to diversify by tackling projects throughout the African continent during the 1980s and 1990s. Its strong network provided a solid base from which to expand.

At the heart of this was the decision to invest in skills training, with the methodologies used in the Moolmans training schools actively replicated in every local community in which the company worked. This proved to be the most effective way to secure mutually beneficial and long-lasting projects.

-

1992

22 July 1992Mining in Limpopo

While more than 90 percent of South Africa’s platinum comes from the North West province, ventures in the neighbouring Limpopo province have also proved successful. The Sandsloot Platinum Mine is located on the edge of a large geological basin.

Aveng Moolmans was awarded the biggest mining tender in Africa to date and quickly brought its earth-moving capabilities to Sandsloot in 1992. The project ran for seven years, bringing many of the company’s senior managers into the fray and securing solid grounding for expansion into the rest of Africa.

-

2000

22 July 2000Montecasino changes the entertainment landscape

Montecasino, the iconic entertainment centre in Fourways, Johannesburg, built by Aveng Grinaker-LTA, opened its doors in 2000. The popularity of the complex grew rapidly, and today it attracts nearly 10 million visitors a year. As early as 2006 plans were developed to extend the complex at a cost of R260 million, including building additional hotel rooms and parking spaces.

These developments were designed to serve the entertainment needs of an influx of guests, who would also find world-class accommodation in a new, four-storey,179-room hotel.

-

2003

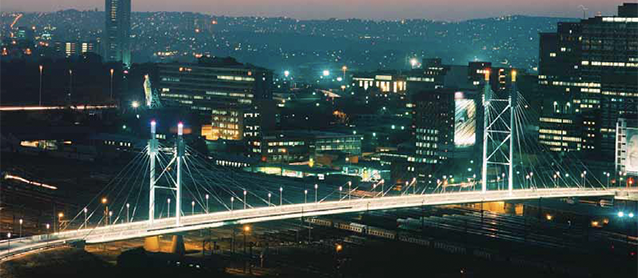

22 July 2003Nelson Mandela Bridge completed

The early 2000s saw plans to rejuvenate Johannesburg’s inner city, beginning with the Newtown precinct that lies adjacent to the central business district (CBD). It was proposed that a bridge be constructed to link the CBD with Braamfontein – and thereby the rest of Johannesburg – as this would draw new interest to the historical centre of town. Bearing the name of an icon, the bridge itself would need to be an iconic addition to the city skyline.

Today, the Johannesburg skyline would seem incomplete without this landmark structure. It has become a proud centrepiece, synonymous with the rejuvenated inner-city culture. Indeed, the bridge links some of Johannesburg’s most well-known cultural attractions, such as the Constitutional Court and the Civic Theatre, with Mary Fitzgerald Square and the Market Theatre.

-

2004

22 July 2004Alternate energy focus

On the North Island of New Zealand lies Manawatu Gorge, a stunning passage with the unusual feature of a water gap, which runs directly through the surrounding mountain ranges. The gorge is also known as Te Apiti, which means “the narrow passage” in Maori, the language traditionally associated with the region.

Built by McConnell Dowell, Te Apiti Windfarm started generating power for the national grid in July 2004. The farm forms part of a larger carbon offset project, with New Zealand’s combined windfarm capacity reaching above 300 megawatts. It is the largest windfarm in the Southern Hemisphere.

-

2008

22 July 2008FNB stadium – a showpiece

When South Africa was announced as the host of the 2010 FIFA World Cup, authorities decided that a new stadium befitting the prestigious tournament would be a necessary investment.

“The jewel of Africa”, as it is now known, prioritises the experience offered to spectators, every seat guarantees an unrestricted view of the pitch. The stadium required 90 000 cubic metres of concrete, 10 000 tonnes of reinforcing steel, nine million bricks and 13 000 tonnes of structural steel. Community upliftment was an integral part of the project, which provided just under 5 000 jobs for members of local communities.

-

2013

22 July 2013The Adelaide Desalination Plant, Australia

South Australia is one of the driest regions on the continent and frequently experiences water shortages as a result. In 2009 the South Australian government outlined several key components that would secure an independent and sustainable water supply for the region.

The Adelaide Desalination Plant treats water through the process of reverse osmosis and drew on McConnell Dowell’s multi-disciplinary strengths. Construction required earthworks, civil structures, marine works, tunnelling, as well as mechanical, electrical and building works. The plant became fully operational in early 2013 and can provide up to 100 gigalitres of drinkable water a year – half of Adelaide’s current water needs.

-

2017

22 July 2017The perfect storm

- Write-down of R5,1 billion in uncertified revenue triggered by under-recovery of QCLNG claims

- Board and executive management changes

- McConnell Dowell restructured under new management

- Aveng Capital Partners infrastructure investments sold to empowerment group Royal Bafokeng Holdings for R860 million

-

2019

22 July 2019Disposal of non-core assets

- Announced sale of Aveng Infraset to 100% black-owned Colossal Africa Consortium for R180 million

- Repaid R200 million bank debt

- Aveng Rail sold to 100% black-owned Mathupha Capital for R133 million

- Aveng Water sold to 100% black-owned Infinity Partners for R85 million

- Dynamic Fluid Control to 100% black-owned Copaflo Fluid Control, for R114 million

- Duraset Alrode to Videx for R50 million

- Rand Roads to Ultra Asphalt for R37,5 million

- Ground Engineering (GEL) to GEL’s management and another shareholder for R7,5 million

- Announced sale of Building and Civil Engineering to 100% black-owned Laula Consortium for R100 million

- Repaid R100 million bank debt

- Renegotiated bank debt

- Announced sale of Mechanical and Electrical to Laula Consortium for R72 million

-

2024

22 July 2024Operational epicentre of Aveng moved to Australia

Aveng undergoes a major leadership change with the retirement of Sean Flanagan and the appointment of Scott Cummins into the CEO role.

The company also announces the shift of its operational epicentre to Australia, while maintaining its listing on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange.

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul

- 22 - Jul